- Animal migration tracking: how did we get to bee backpacks? | Alphr 082615

[A good overview of the history of animal tracking technology, with links] “Tiny bee backpacks… These microsensors have been glued to the backs of 10,000 honey bees to try to figure out the causes of colony collapse. The battery in each is powered by the vibration of the bee, meaning it will keep transmitting until the bee dies. | Receivers placed around bee hives track data from each sensor, including how far they travel and how long they’re gone, but also how each bee interacts with factors that have been blamed for the fall of bees: exposure to pesticides; air pollution; water contamination; weather; and diet. | Each 2.5mm x 2.5mm pack weighs 5.4 milligrams, which sounds like nothing, but it’s the equivalent of you or me having two 13in Macbook Pros strapped to our backs. And we don’t even have to fly anywhere.”

- Coop’s Scoop: Citizen science to study your dog, because your dog studies you – CitizenSci 082315

Caren Cooper: “Neanderthals were in Europe and Asia for two hundred thousand years, but began their demise as our people, Homo sapiens, expanded beyond Africa. Like Neanderthals, humans hunted, used tools, were pyrotechnic, and social enough to have cliques. Some researchers suspect that humans had one advantage that Neanderthals lacked: the precursor to (hu-)man’s best friend, the domesticated dog. Less wild than wolves, more wild than today’s collie, early humans likely survived an epoch of environmental change with the help of furry friends that were eventually domesticated as dogs. | That’s the argument made by Pat Shipman in her book, The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction. Shipman, a retired adjunct professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University, explores the evidence for a historic alliance between dogs and humans and what such an alliance enabled, including, for example, the hunting and transport of wooly mammoths. | Our longstanding relationship with dogs has led researchers in animal behavior and comparative psychology find our loyal companions (Canis familiaris) to be an excellent subject for studies of the mind. Some animal behaviorists prefer to study non-human primates because these are evolutionarily the closest relatives to our species. Even though we share more DNA with chimps, we’ve shared more of our social history with dogs. Now dogs solve social problems more similarly to human toddlers than many primates do. Their domestication process endowed them with skills to understand our verbal and body languages, and to read our emotional states which is something akin to empathy. | Children develop empathy after four. Dogs don’t necessarily have the mental capacity to imagine walking their paws in a person’s shoes, but they have emotional contagion, like toddlers. Emotional contagion means they can respond to the emotions of others without fully understanding what the other is feeling. When dogs display sympathy and behave in comforting ways, it is in response to their owner being sad. When dogs are wary, their owner is giving off a vibe of distrust or fear. When a dog is humping, their owner is feeling…well, never mind, that behavior is an independent, normal part of a dog’s life. | Dogs are so good at reading our intentions, practically reading our mind, that you probably can’t deceive your dog. Your dog, however, has no qualms about being deceptive. According to early findings in Dognition, dogs most bonded to their owners are most likely to have intelligent disobedience, such as watching their owners closely enough to capitalize on a distracted moment to steal food. | In The Genius of Dogs: How dogs are smarter than you think, by Brain Hare and Vanessa Woods, they suggest that natural selection favored those individual early dogs that were best able to figure out human intentions. Selection was not necessarily favoring the most intelligent dogs, but those with strong skills at social cognition. Through it all, dogs have been paying attention to us and now they are better at understanding us than we are at understanding them. No wonder we are the ones scooping up the poop. Maybe it was their master plan since the dawn of time.”

- From his unique perch, Minnesota bird lover surveys the state | Minnesota Public Radio News 082415

“Birds are beautiful objects,” Bob Janssen said. “They’re everywhere you go. They are ever-changing, ever-beautiful, ever-intriguing, ever-mysterious. So I became a provincial Minnesota birder.” And even with his magnum opus now in print, Janssen isn’t finished yet. He said he may think up another book about Minnesota birds while he recovers from some knee surgery in coming weeks.

- Five Mystery Birds Among Audubon’s Paintings – The New York Times 082115

Roberta J. M. Olson, curator of drawings at the New-York Historical Society, which has all 435 of Audubon’s watercolor models, listed the five “mystery birds,” as they are often referred to, labeled by Audubon: Townsend’s Finch (identified in a later edition as Townsend’s Bunting), Cuvier’s Kinglet, Carbonated Swamp Warbler, Small-headed Flycatcher and Blue Mountain Warbler. | These birds have never been positively identified, and no identical specimens have been confirmed since Audubon painted them. Ornithologists have suggested that they might be color mutations, surviving members of species that soon became extinct, or interspecies hybrids that occurred only once.

- About Fluidr

Fluidr is a distraction-free way to view and interact with Flickr photos and videos. It was designed to allow you, the viewer, to discover and interact with Flickr photos and videos with as little distraction as possible.

About the Ghost Turtles

150 years after Robert Duncanson painted this luminist scene on the Little Miami River, I stood in the same spot and saw a soft-shelled turtle sunning on a snag. It slipped silently into the water when it heard me. That’s when I knew past is present and destiny, too. That’s when my vision of the Ghost Turtles began. Read more

Ecology of the Senses

Returning to Lake Superior year after year like a migrating loon, I’ve learned the other side of a slow, uncertain process that could be called “going blind.” With the lake as my teacher, I know what lies on the other side. I call it letting go of sight. Read more.

Returning to Lake Superior year after year like a migrating loon, I’ve learned the other side of a slow, uncertain process that could be called “going blind.” With the lake as my teacher, I know what lies on the other side. I call it letting go of sight. Read more.Prayer at Big Creek

![Sandhill cranes land on Platte River sandbar roosts west of Rowe Sanctuary’s Iain Nicolson Audubon Center southwest of Gibbon, Nebraska. [Photo by Lori Porter| Kearney Hub]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/sandhill_cranes_kearneyhub_032015-300x225.jpg) At the threshold of consciousness, as I slipped back and forth between two worlds, I put my mind in the best place I could imagine, a marsh on Lake Erie called Big Creek. I knew I’d find cranes waiting for me. I cannot say whether I prayed for them, or to them, or with them. The cant of words doesn’t matter. I believe in the still, small voice. I believe what the poet Yehuda Amichai said. Gods come and go. Prayer is eternal. Read more

At the threshold of consciousness, as I slipped back and forth between two worlds, I put my mind in the best place I could imagine, a marsh on Lake Erie called Big Creek. I knew I’d find cranes waiting for me. I cannot say whether I prayed for them, or to them, or with them. The cant of words doesn’t matter. I believe in the still, small voice. I believe what the poet Yehuda Amichai said. Gods come and go. Prayer is eternal. Read moreFreedom to Read

![An endangered Whooping crane takes flight. Yhe large bird has a 7-foot wingspan. It is all white except for black wing tips and face markings. In this photo its long neck stretches forward; its wings sweep upward; and its black legs trail straight behind it. [Source: International Crane Foundation]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Whooping-crane-eastern-ICF-080622-300x157.jpg) Whenever I hear sanctimonious pronouncements about woke, parental rights, and banning books, I think of Whooping cranes. In my family, the gawky, audacious, elusive and endangered birds are synonymous with our values about the First Amendment and the freedom to read. Read more.

Whenever I hear sanctimonious pronouncements about woke, parental rights, and banning books, I think of Whooping cranes. In my family, the gawky, audacious, elusive and endangered birds are synonymous with our values about the First Amendment and the freedom to read. Read more.Sister, Teacher, Pathfinder

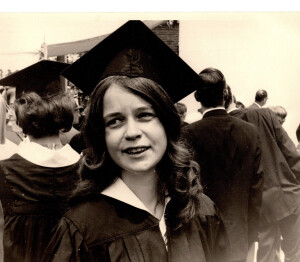

A guidance counselor in high school told my sister Diana, “With your eye problems you will never make it in college. Just forget about it. Get married. Raise a family.” That advice only deepened her determination. She did it all in due time, in her own way –college, marriage, family. She became a guidance counselor herself. She certainly was the most important guide and pathfinder in my life. Read more.

A guidance counselor in high school told my sister Diana, “With your eye problems you will never make it in college. Just forget about it. Get married. Raise a family.” That advice only deepened her determination. She did it all in due time, in her own way –college, marriage, family. She became a guidance counselor herself. She certainly was the most important guide and pathfinder in my life. Read more.Flaneur & Bouquiniste

![Mark Willis peruses a 1745 volume by Voltaire at a bouquiniste book stall on the banks of the Seine in Paris. He wears a brown leather jacket and checkered flat cap. He holds the open book in his hands. Rows of old books are seen on shelves behind him. [2005 photo by Ms. Modigliani]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/mw_bouquiniste_05-300x225.jpg) I remember the book I held in my hands that day. I remember the feel of its time-warped, water-stained pages. I remember its murky, moldy river smell, call it the book’s bouquet, suggesting years of storage on the banks of the Seine. Had I bought it then, I could feel and smell it now and know it from a hundred other books in my library. Read more.

I remember the book I held in my hands that day. I remember the feel of its time-warped, water-stained pages. I remember its murky, moldy river smell, call it the book’s bouquet, suggesting years of storage on the banks of the Seine. Had I bought it then, I could feel and smell it now and know it from a hundred other books in my library. Read more.R & K: A Rant

Marjorie Taylor Green auditioned for R&K’s Authoritarian It Girl at the 2023 State of the Union address. She and her Republican colleagues yelled like Tarzan swinging through the trees as they jeered and booed the President’s speech. Read Rants & Kisses.

Marjorie Taylor Green auditioned for R&K’s Authoritarian It Girl at the 2023 State of the Union address. She and her Republican colleagues yelled like Tarzan swinging through the trees as they jeered and booed the President’s speech. Read Rants & Kisses.R & K: A Kiss

Songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David. Singers like Dione Warwick and Dusty Springfield. What Do You Get When You Fall in Love? The Look of Love. I Say a Little Prayer. I sit in the car’s back seat and listen. I’m glad it’s dark. I’d be embarrassed if anyone could see the dreamy look on my face. Read Rants & Kisses.

Songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David. Singers like Dione Warwick and Dusty Springfield. What Do You Get When You Fall in Love? The Look of Love. I Say a Little Prayer. I sit in the car’s back seat and listen. I’m glad it’s dark. I’d be embarrassed if anyone could see the dreamy look on my face. Read Rants & Kisses.