I will never forget the book. I wanted to touch it reverently. I don’t remember wearing white cotton gloves, but I probably did. Back then, gloves were a necessary precaution taken to preserve the condition of old books. Today, librarians consider gloves to be misguided props in the theater of rarity and respect. The practice poses more hazards than it prevents.

I will never forget the book. I wanted to touch it reverently. I don’t remember wearing white cotton gloves, but I probably did. Back then, gloves were a necessary precaution taken to preserve the condition of old books. Today, librarians consider gloves to be misguided props in the theater of rarity and respect. The practice poses more hazards than it prevents.

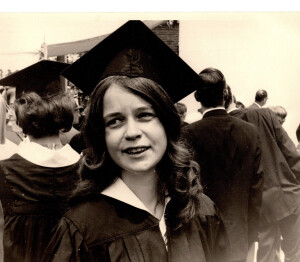

The year was 1978. The place was the rare book collection at Berea College in Kentucky. And the book?

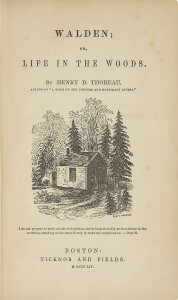

It was an 1854 first edition of Walden by Henry David Thoreau. By 1978 I knew already that it was the most influential book I ever would read. I’ve read it completely half a dozen times, and I read some substantial part of it every year. I quote from Walden, chapter and verse, almost every day. Now I have an audio edition on the phone in my pocket. What would Henry say about that? Since I have rambling, one-sided conversations with him every time I walk to my office at Ellis Pond, I expect he will let me know.

So… back to 1978 and the rare book in my gloved hands. It was one of 1,000 copies printed by the Boston publisher Ticknor and Fields. It wasn’t exactly a best-seller in its time. Shortly before his death in 1862, Thoreau boxed up 800 remaindered copies, observing dryly, “I am the proud owner of a library with more than a thousand volumes. I wrote most of them myself.”

The book I held did not appear to be well-read. It had no dog-eared pages, cracked spine, or owner’s inscription. If I opened it randomly to one page or another, I saw no marginalia penned in some book lover’s fastidious hand. I didn’t thumb through it with clumsy white gloves, though, so rare book librarians can relax.

I didn’t thumb through it to find a cherished quote because I wouldn’t see it anyway. I’d lost the ability to read printed books several years earlier. Touching the book was enough. What I really wanted to do was hold the book close to my nose to imbibe it’s bouquet like a snifter of aged Cognac. That would have shocked and embarrassed the archivist standing next to me, who was an old friend. She had secured access for me on her good word when the Berea College library was closed for Kentucky Derby Day.

What I remember most about the book’s physical appearance was the vivid title page illustration of the shack at Walden Pond. It was drawn by Thoreau’s sister Sophia. I didn’t know that an authentic representation existed, drawn back in the day by an artist who had seen the shack with her own eyes.

Sophia’s drawing in that moment reminded me of the very first time I encountered the name Thoreau. I read it in the Amateur Naturalist’s Handbook when I was 12 years old. Extolling the value of field biology, its author posed the rhetorical question, “What museum director today has an office in the woods, like Henry Thoreau?” I didn’t know. I liked the idea of an office in the woods. That’s when I decided to figure out how to get one.

Allie Alvis, a.k.a. Book Historia, explains best practices for handling rare books in her YouTube series Bite Size Book History. She concludes, “Glove-free is the way to be.”

Jennifer Schuessler interviewed Alvis and other book curators for a story about “the glove thing” in the New York Times.

![Sandhill cranes land on Platte River sandbar roosts west of Rowe Sanctuary’s Iain Nicolson Audubon Center southwest of Gibbon, Nebraska. [Photo by Lori Porter| Kearney Hub]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/sandhill_cranes_kearneyhub_032015-300x225.jpg)

![An endangered Whooping crane takes flight. Yhe large bird has a 7-foot wingspan. It is all white except for black wing tips and face markings. In this photo its long neck stretches forward; its wings sweep upward; and its black legs trail straight behind it. [Source: International Crane Foundation]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Whooping-crane-eastern-ICF-080622-300x157.jpg)

![Mark Willis peruses a 1745 volume by Voltaire at a bouquiniste book stall on the banks of the Seine in Paris. He wears a brown leather jacket and checkered flat cap. He holds the open book in his hands. Rows of old books are seen on shelves behind him. [2005 photo by Ms. Modigliani]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/mw_bouquiniste_05-300x225.jpg)