- Flight Maps: Chapter 1 – THE PASSENGER PIGEON EXTINCTION

Excerpt from “Flight Maps: Adventures With Nature in Modern America” (1999) by Jennifer Price: “The colonists appreciated pigeons in other ways, too. They valued the wildlife and lands around them for many reasons at once. Wild pigeons were economic resources to shoot and eat and to sell. They were also a natural wonder, and an occasion for celebration. | In fact, the wild pigeons fueled the widely shared conviction that Americans could never deplete their resources. While in the 1990s, that logic may be hard to grasp, colonists perhaps would have had to summon even greater imaginative powers to envision the comparatively empty, devastated landscapes that have become so familiar to us. Six-foot lobsters in the surf, rivers swarming with salmon and covered with ducks, woods "abounding with deer, and the trees with singing birds": the abundance of North American wildlife in the 1600s and early 1700s sounds almost as biblical today as it must have seemed to European settlers (with decidedly more biblical turns of mind) who left behind Old World lands that had been overhunted for centuries, and where the upper classes held game preserves under strict control. While even the first settlers depended primarily on domestic European crops and livestock, they supplemented freely with wild game. Occasionally, when the crops failed due to drought or an early freeze, colonists relied on hunting as an essential stopgap. Reports to England seldom failed to mention the free and abundant game, or the wild pigeons: "I have seen them fly as if the airy regiment had been pigeons, seeing neither beginning or ending, length or breadth of these millions of millions." | To shoot and eat a game bird in the American colonies became a defining New World act. Think of Thomas Morton in Massachusetts in the 1620s, reporting back that he had seen a thousand geese "before the mouth of my gun," and had fed his "dogs with as fat geese there as I have ever fed upon myself in England." The geese were American. So was their easy abundance, their impressive lard-to-bone ratio, their frequent presence on the table, and not least, one’s freely held, unregulated right to shoot them. Going off to shoot pigeons or geese, and hauling strings of them back home, became activities resonant with one’s experience of daily American life. The hunt meant so much more than mere utilitarian gain. To go hunting was to tap into the continent’s bounty, to supplement the table, to exercise your skill with a shotgun, perhaps to band together with neighbors after plowing. You also expressed your rights or ideals in a fledgling polity. Hunting was at once an ecological, economic and political thing to do, a social event and a sport. It was like telling a story to yourself, about yourself. Not actually a story told out loud: the hunt was more a cultural play, a story acted out in the course of day to day living, about your relationships to birds but also to one another—a story about where you lived, who your neighbors were, how you made a living and what you believed. In the course of their encounters with pigeons—as they invested nature with small worlds of meaning—people were also doing a great deal of thinking about themselves. | You could make especially emphatic meanings with pigeons. A waterfowl hunt brought together a few neighbors, but a pigeon hunt, which mobilized an entire county, enacted a more powerfully meaningful story about the social ties that knit these rural communities together. Likewise, to bag "thirty, forty, and fifty pigeons at a shot" was practically to caricature your political claims to American game. And if settlers relied on other game animals during lean times, the pigeon hunts, when necessary, enacted a more dramatic cultural play about the weak points of the colonial economy: in 1769, during a widespread crop failure in Vermont, pigeons staved off starvation for thirty thousand people for six weeks. Above all, more than any other piece of the New World, pigeon flocks symbolized the continent’s natural bounty. The salmon, geese and lobsters inspired believe-it-or-not reports, but the pigeons’ abundance seemed quite literally biblical, like "the quails that fell round the camp of Israel in the wilderness." Eventually the pigeons’ disappearance would symbolize Americans’ rapid conversion of a landscape of abundance into one of scarcity. The pigeons would narrate that story with special effectiveness, too."

About the Ghost Turtles

150 years after Robert Duncanson painted this luminist scene on the Little Miami River, I stood in the same spot and saw a soft-shelled turtle sunning on a snag. It slipped silently into the water when it heard me. That’s when I knew past is present and destiny, too. That’s when my vision of the Ghost Turtles began. Read more

Ecology of the Senses

Returning to Lake Superior year after year like a migrating loon, I’ve learned the other side of a slow, uncertain process that could be called “going blind.” With the lake as my teacher, I know what lies on the other side. I call it letting go of sight. Read more.

Returning to Lake Superior year after year like a migrating loon, I’ve learned the other side of a slow, uncertain process that could be called “going blind.” With the lake as my teacher, I know what lies on the other side. I call it letting go of sight. Read more.Prayer at Big Creek

![Sandhill cranes land on Platte River sandbar roosts west of Rowe Sanctuary’s Iain Nicolson Audubon Center southwest of Gibbon, Nebraska. [Photo by Lori Porter| Kearney Hub]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/sandhill_cranes_kearneyhub_032015-300x225.jpg) At the threshold of consciousness, as I slipped back and forth between two worlds, I put my mind in the best place I could imagine, a marsh on Lake Erie called Big Creek. I knew I’d find cranes waiting for me. I cannot say whether I prayed for them, or to them, or with them. The cant of words doesn’t matter. I believe in the still, small voice. I believe what the poet Yehuda Amichai said. Gods come and go. Prayer is eternal. Read more

At the threshold of consciousness, as I slipped back and forth between two worlds, I put my mind in the best place I could imagine, a marsh on Lake Erie called Big Creek. I knew I’d find cranes waiting for me. I cannot say whether I prayed for them, or to them, or with them. The cant of words doesn’t matter. I believe in the still, small voice. I believe what the poet Yehuda Amichai said. Gods come and go. Prayer is eternal. Read moreFreedom to Read

![An endangered Whooping crane takes flight. Yhe large bird has a 7-foot wingspan. It is all white except for black wing tips and face markings. In this photo its long neck stretches forward; its wings sweep upward; and its black legs trail straight behind it. [Source: International Crane Foundation]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Whooping-crane-eastern-ICF-080622-300x157.jpg) Whenever I hear sanctimonious pronouncements about woke, parental rights, and banning books, I think of Whooping cranes. In my family, the gawky, audacious, elusive and endangered birds are synonymous with our values about the First Amendment and the freedom to read. Read more.

Whenever I hear sanctimonious pronouncements about woke, parental rights, and banning books, I think of Whooping cranes. In my family, the gawky, audacious, elusive and endangered birds are synonymous with our values about the First Amendment and the freedom to read. Read more.Sister, Teacher, Pathfinder

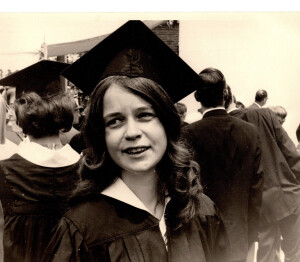

A guidance counselor in high school told my sister Diana, “With your eye problems you will never make it in college. Just forget about it. Get married. Raise a family.” That advice only deepened her determination. She did it all in due time, in her own way –college, marriage, family. She became a guidance counselor herself. She certainly was the most important guide and pathfinder in my life. Read more.

A guidance counselor in high school told my sister Diana, “With your eye problems you will never make it in college. Just forget about it. Get married. Raise a family.” That advice only deepened her determination. She did it all in due time, in her own way –college, marriage, family. She became a guidance counselor herself. She certainly was the most important guide and pathfinder in my life. Read more.Flaneur & Bouquiniste

![Mark Willis peruses a 1745 volume by Voltaire at a bouquiniste book stall on the banks of the Seine in Paris. He wears a brown leather jacket and checkered flat cap. He holds the open book in his hands. Rows of old books are seen on shelves behind him. [2005 photo by Ms. Modigliani]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/mw_bouquiniste_05-300x225.jpg) I remember the book I held in my hands that day. I remember the feel of its time-warped, water-stained pages. I remember its murky, moldy river smell, call it the book’s bouquet, suggesting years of storage on the banks of the Seine. Had I bought it then, I could feel and smell it now and know it from a hundred other books in my library. Read more.

I remember the book I held in my hands that day. I remember the feel of its time-warped, water-stained pages. I remember its murky, moldy river smell, call it the book’s bouquet, suggesting years of storage on the banks of the Seine. Had I bought it then, I could feel and smell it now and know it from a hundred other books in my library. Read more.R & K: A Rant

Marjorie Taylor Green auditioned for R&K’s Authoritarian It Girl at the 2023 State of the Union address. She and her Republican colleagues yelled like Tarzan swinging through the trees as they jeered and booed the President’s speech. Read Rants & Kisses.

Marjorie Taylor Green auditioned for R&K’s Authoritarian It Girl at the 2023 State of the Union address. She and her Republican colleagues yelled like Tarzan swinging through the trees as they jeered and booed the President’s speech. Read Rants & Kisses.R & K: A Kiss

Songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David. Singers like Dione Warwick and Dusty Springfield. What Do You Get When You Fall in Love? The Look of Love. I Say a Little Prayer. I sit in the car’s back seat and listen. I’m glad it’s dark. I’d be embarrassed if anyone could see the dreamy look on my face. Read Rants & Kisses.

Songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David. Singers like Dione Warwick and Dusty Springfield. What Do You Get When You Fall in Love? The Look of Love. I Say a Little Prayer. I sit in the car’s back seat and listen. I’m glad it’s dark. I’d be embarrassed if anyone could see the dreamy look on my face. Read Rants & Kisses.