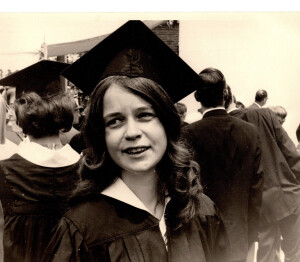

By Rachel Cusk : Perhaps with no clearer motive than F. Scott Fitzgerald’s observation that “France has the only two things toward which we drift as we grow older — intelligence and good manners,” we packed up our possessions during the last dark days of one December and decided to move to Paris. It was pleasant, I had often been told, for a writer to live somewhere where reading and writing were accorded the highest respect, and it was true that — in Paris at least — these were semipublic activities: In every park and cafe, on the Metro and on the benches along the Seine, people were openly engaged in what for me had always been the most private and solitary of occupations. Bookstores still held their ground here among the shopfronts, and the deification of French writers living and dead was evinced everywhere in street names and statues and advertising hoardings for new novels. I listened on the radio to an astronaut reading passages aloud from Marguerite Duras from his space station to his earthbound audience below.

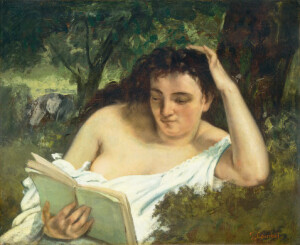

Then, last October, the writer Annie Ernaux won the Nobel Prize for Literature, the first Frenchwoman ever to do so. We had been in France for nearly two years, and amid the alternating sensations of regeneration and disarray that this upheaval had inevitably incurred, Annie Ernaux had come to represent for me a troubling point of constancy. During my initial months in Paris, when it seemed for the first time in my life that lying on a sofa reading a book was something I was not only permitted but encouraged to do, I made my way slowly in my clumsy French through one slim text after another: “A Man’s Place,” “A Woman’s Story,” “Simple Passion,” “The Possession,” “The Years.” The story they told, rigorously excluding anything that did not directly pertain to it, was that of Annie Duschene (Ernaux’s maiden name), only child of a working-class French couple who ran a humble café-epicerie in Yvetot, a small town in Normandy.

By means of scholarly excellence, Annie claws her way out of the mire of her origins to teacher-training college, marries the first man who presents himself, is submerged in a bourgeois purgatory as housewife and mother and slowly breaks her way out of that new prison by writing books — books that try to stop time by questioning and reconstructing as precisely as they can the events that have brought her to the existence she is now leading. Who is she, and where has she come from? Who were her parents, and why did they live as they did? Why did she act in certain ways as she became free of them, and to what degree is her life the consequence of those actions? Has she ever lived consciously even for one minute, or is this task of writing and reconstruction the effort to apply consciousness to blind fate?

Despite the differences — of nationality, generation, social class, familial situation — between my own life and that of Annie Ernaux, I found myself plunged as I read into a more and more profound state of recognition. Yet what I seemed to be recognizing were things that no one generally admits. Ernaux’s honesty had the effect of illuminating a profound and unsuspected lack of freedom in her reader. How, through the simple story of her origins, had she laid her hand so surely on the human tragedy of our ability to make ourselves unfree? The answer perhaps lay in her faith in writing as a sacred and transcendent activity. She believed in writing as some people believe in religion, as a sphere where the self, the soul, is entitled to find refuge.

Source: Annie Ernaux Has Broken Every Taboo of What Women Are Allowed to Write – The New York Times

![Sandhill cranes land on Platte River sandbar roosts west of Rowe Sanctuary’s Iain Nicolson Audubon Center southwest of Gibbon, Nebraska. [Photo by Lori Porter| Kearney Hub]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/sandhill_cranes_kearneyhub_032015-300x225.jpg)

![An endangered Whooping crane takes flight. Yhe large bird has a 7-foot wingspan. It is all white except for black wing tips and face markings. In this photo its long neck stretches forward; its wings sweep upward; and its black legs trail straight behind it. [Source: International Crane Foundation]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Whooping-crane-eastern-ICF-080622-300x157.jpg)

![Mark Willis peruses a 1745 volume by Voltaire at a bouquiniste book stall on the banks of the Seine in Paris. He wears a brown leather jacket and checkered flat cap. He holds the open book in his hands. Rows of old books are seen on shelves behind him. [2005 photo by Ms. Modigliani]](https://www.ghostturtles.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/mw_bouquiniste_05-300x225.jpg)